Maximizing Expected Growth

I will give you +120 odds for a coin to land heads. That means that if you bet $100

and the coin lands heads, you will get your initial $100 back and an additional $120,

totaling $220. If the coin lands tails, you lose the $100. Similarly, if you bet X dollars,

you would gain 1.2X dollars or lose X dollars.

You may realize that this is an incredible bet for you.

We can look at this mathematically using the idea of Expected Value. In this situation,

Expected Value is how much you would end up with on average if you were to make this

bet many times. We can calculate the Expected Value by summing

the value of each outcome times the probability of that outcome. For betting $100

in this example, that would be: \[E = 220(0.5) + 0(0.5) = 110\] So if you bet $100,

on average, you would end up with $110, which would be great! This is an example of

what is called a "plus EV" bet, which means that, on average, you will win money.

Seems simple so far; if I walked up to you on the street and gave you this opportunity,

mathematically you should make the bet. But what if I gave you $100 for your 'bankroll' and said you can

bet on a coin flip with +120 odds as many times you want? The only stipulation is that

you have to use that $100 or money made off previous bets, you cannot add external

money to your bankroll. This doesn't seem like that bad of a stipulation.

Actually, this situation seems even better than the first hypothetical because you can make as many

plus EV bets as you want! So now we arrive at the pivotal question:

How much should you bet?

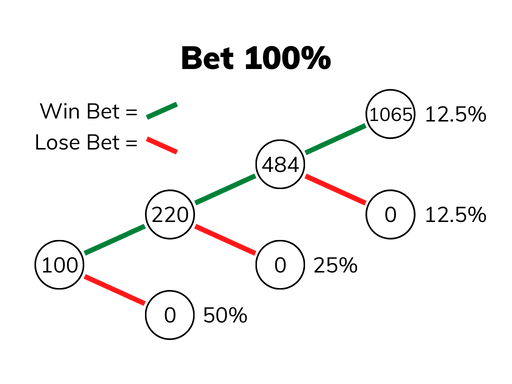

Let's start by testing the extreme. Let's bet all of it, and if you win, bet it all again!

As you can see below, after 3 bets there's only a 12.5% chance that you have any money left.

You might get lucky one or two times, but the more you keep betting, the more likely

you are to bust and lose all of your money.

But I thought all of these bets were

plus EV?? And they are! Which is why in the rare case you did win three times in a row,

you would end up with $1065, meaning your overall Expected Value is $133. This is a good

increase, but it is rare that you realize this gain, and it becomes exponentially rarer

the more times you bet. So if you plan on betting in perpetuity in order to make this good

bet as many times as possible, there is effectively a 0% chance that you will realize that

great Expected Value.

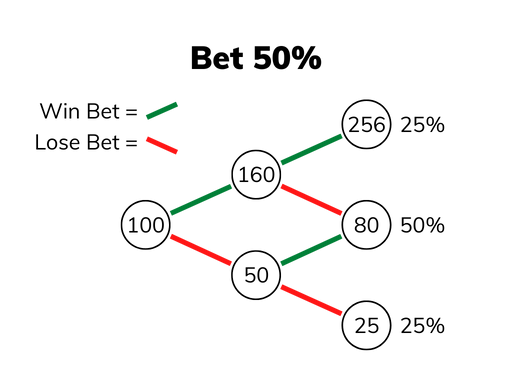

Let's look at another simple case. Let's keep betting half of whatever you have left.

Looking below, we can notice several things. Unfortunately, the most likely outcome

is that you lose money. This can, again, be explained by the concentration of value

gained when you are lucky.

Another thing that you might notice is that your bankroll increases by a constant ratio

when you win, regardless of what your bankroll is at that point: \[\frac{160}{100} = \frac{256}{160} = \frac{80}{50} = 1.6\]

Similarly, your bankroll decreases by a constant ratio when you lose: \[\frac{100}{50} = \frac{160}{80} = \frac{50}{25} = 0.5\]

This leads to another observation (because multiplication is Commutative): the order

of wins and losses doesn't matter. Whether you win then lose, or lose then win, you end

up with: \[$100(1.6)(0.5) = $100(0.5)(1.6) = $80\]

Now we can start to create a formula for our average expected growth ratio.

(I will use growth ratio, \(G\), to be the ratio of the amount in your bankroll after betting to the amount before betting.

Growth rate, which is used interchangeably with percent change, is just equal to the growth ratio minus one and divided by 100.)

If you succeed \(S\) times and fail \(F\) times for this bet, your remaining money would be:

\[G = $100{(1.6)}^{S}{(0.5)}^{F}\]

Let's say you make this bet 10 times, which is not very many

compared to the infinite amount of times you can make this bet. In this case,

the most likely outcome is 5 successes and 5 failures.

This would mean that you are most likely to have:\[G = $100{(1.6)}^{5}{(0.5)}^{5} = $32.8\]

But couldn't you get lucky? If you happen to get more than 5, you would gain money, and that isn't

that unlikely, right?

There is a statistical concept that will help us here called the law of large numbers.

This says that as you make more and more bets, in the long run, the proportion of

successes will equal their likelihood. To be mathematically rigorous:

\[\lim_{N \to \infty}\sum_{i=1}^{N}{\frac{{x}_{i}}{N}} = \bar{x}\]

So maybe you get lucky with your first 10 and get 7 heads, a proportion of 0.7!

If you have average luck on your next 90 coin flips, your overall total would be 52 or a proportion of 0.52.

And the more you bet, the higher the likelihood will be that your rate of success

is close to the true probability, which, in this case, is 0.5. So, if you make this bet 100 times,

this is the most like outcome:\[G = $100{(1.6)}^{50}{(0.5)}^{50} = $0.0014\]

This may be off by a few orders of magnitude depending on how lucky you are,

but if you keep betting, the law of large numbers will have its way\(^{*}\).

\(^{*}\)One common misunderstanding is the gambler's fallacy which assumes that

'nature' will 'purposefully' compensate for what the luck has been so far,

but a more accurate way to think about it is, however lucky you are on the

first 10 flips will be drowned out by your luck on the next 1,000 flips which

will be drowned out by the luck on your next 1,000,000 flips.

And with more flips, the distribution of outcomes is much narrower:

it is very common to get 6 heads out of 10, but basically impossible to get

600 heads out of 1000.

Understanding the law of large numbers is very important because - in the short run -

it feels like you can get lucky and realize the good Expected Value.

However, in the long run you will neither be very lucky nor very unlucky.

We can use this to our advantage, or to our detriment.

Now we can create a formula for the average expected growth ratio. If the total number of attempts

is \(S + F = N\), then the average or expected growth ratio, \(\bar{G}\), can be

calculated by taking the Nth root of the formula for growth rate divided by the initial amount.

So for this bet that would be:

\[\bar{G}={\Big(\frac{100{(1.6)}^{S}{(0.5)}^{F}}{100}\Big)}^{\frac{1}{N}} = {(1.6)}^{\frac{S}{N}} {(0.5)}^{\frac{F}{N}} = {(1.6)}^{s} {(0.5)}^{f}\]

Here \(s\) and \(f\) are the rates of success and failure. We can then calculate that

the expected growth ratio for betting half of what you have left on the incredible +120 coin flip is:

\[{(1.6)}^{0.5} {(0.5)}^{0.5} = 0.894\]

which translates to a growth rate of -10.6% per bet.

This is terrible. For context, the stock market growth rate is roughly positive 10% annually.

But we don't even have to worry about how high the growth rate is, because right now it's negative!

Okay, so even though this bet should be really good, betting half of our bankroll each

time lost us money in the long run. So, what if we bet only 5 percent?

First, let's calculate the ratios. With +120, if you were to bet a 5 percent, the ratio for a success, \({R}_{s}\),

and failure, \({R}_{f}\), would be: \[{R}_{s} = 0.95 + (0.05 + (1.2)0.05) = 1.06\] \[{R}_{f} = 0.95 + 0 = 0.95\]

In general, if we let \(R\) be the rate of return and \(p\) be the proportion that we bet,

then those ratios would be: \[{R}_{s} = (1-p) + (p + (R)p) = 1 + (R)p\] \[{R}_{f} = (1-p) + 0 = 1-p\]

Back to our example, if we plug in our ratios and success/failure rates, we find that:

\[{(1.06)}^{0.5} {(0.95)}^{0.5} = 1.0035\]

A positive growth rate! A 0.35% growth rate to be precise. This is wonderful!

Now we finally have a way of taking advantage of the plus EV bet.

And in this hypothetical we can bet an infinite amount of times. Therefore,

as long as the growth is positive, we will be able to infinitely grow our money!

However, this is the real world. What can we learn from this hypothetical?

Expected growth rate is different than Expected Value, and, if we assume that

we are not adding money to our initial bankroll, we want to maximize our

expected growth rate for every bet that we make so that, in aggregate,

our bankroll is growing as quickly as possible.

So, how can we maximize our expected growth rate? Let's start with the formula

that we found for growth rate.

If we know the odds and the true probability of any bet, the growth rate will be:

\[\bar{G} = {(1 + (R)p)}^{s} {(1-p)}^{f}\]

Using calculus, we can take the derivative of that equation with respect to p,

set it equal to 0, and solve for p. The resulting equation will tell us the proportion

of our bankroll that we should bet: \[p = s - \frac{f}{R}\]

This equation is so simple! Now we can plug in the values that we have to find that,

for this hypothetical, the optimal proportion is: \[p = 0.5 - \frac{0.5}{1.2} = \frac{1}{12}\]

If we plug this into our original equation,

we find that the growth ratio that we get when we bet this amount is:

\[\bar{G} = {\Big(1 + (1.2)\frac{1}{12}\Big)}^{0.5} {\Big(1-\frac{1}{12}\Big)}^{0.5} = 1.0042\]

This is a 0.42% growth rate. This may seem only a little bit better than the 0.35% from before, but,

because growth is exponential, even this small difference will compound quickly.

So, if we came across a bet with the numbers from the hypothetical, where we think

there is a 50% chance that team A wins, and their moneyline (betting odds for them

winning) is +120, we know that we should bet 1/12 of our

bankroll in order to best take advantage of it. Granted, the hard part is

actually knowing what the probabilities are or even finding bets that you think are

plus EV (they must be plus EV to have a positive maximum growth rate). But now you

know what to do if you find yourself wanting to bet as efficiently as possible.

Now, there is a reason that I skipped over the calculus used to derive the equation

other than the fact that there are very few that would want to see it, and that

is because as long as you have the formula for the value that you want to maximize,

there are many different computer algorithms that can just calculate the answer without

needing to take the derivative. These maximization algorithms are very powerful,

they can actually solve for multiple variables at once! And why do I bring up this

capability? Because we can use it to grow our bankroll even faster!

Notice again how incredible that initial bet was. It was a 4.5% edge, which,

in the real world, is going to be uncommon. So how can we make up for this

using the aforementioned maximization algorithms? We can make multiple bets at once!

I will start with a situation that you might want to bet on, but is probably not

an optimal use of your bankroll: futures. Futures are usually season-long bets

where there are more than two possible winners. For example, you can bet on which

player will end up being voted the MVP of the season and you can bet on multiple

different players. Betting futures may be fun, but I do not recommend betting

them if you are just trying to increase your bankroll for multiple reasons:

So why do I even bring up futures? First, I wanted to warn you that they are more for fun than for growing your bankroll. Second, some of you will bet on them anyway. Third, the formula used to optimize those bets will be very illustrative.

So, how do we build a formula for expected growth ratio when you can bet on multiple potential winners for the same event? Let's use the example of betting on which player will win MVP at the end of the year. We can start by saying that we have these inputs for who is going to win MVP. They are based on combining players from the actual 2020 MVP race and using PFF's predictions for the 'True' probabilities.

| Player | Betting Line | Return Ratio | Implied Probability | True Probability | Expected Value Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | +700 | 7.0 | 0.125 | 0.233 | 1.86 |

| B | +170 | 1.7 | 0.370 | 0.454 | 1.23 |

| C | +550 | 5.5 | 0.154 | 0.110 | 0.72 |

| D | +800 | 8.0 | 0.125 | 0.050 | 0.45 |

| E | +450 | 4.5 | 0.182 | 0.043 | 0.24 |

Let's set up an equation, like we did for the coin flip, for betting on player 1. Since we are treating it as if there are only two outcomes (player 1 wins MVP or they don't) we can use the same formula we used before. \[\bar{G} = {(1 + (R)p)}^{s} {(1-p)}^{f} = {(1 + 7p)}^{0.233} {(1-p)}^{1-0.233}\] Instead of using calculus, I will use the maximization algorithm described above to solve for the optimal betting proportion and the resulting growth ratio. If you want to see how I run these calculations in a Google Colab notebook, click here. For this player, the optimal betting proportion is 0.123 and the resulting growth ratio is 1.045 or a 4.5% growth rate. Let's do this again for each of the other players and add it all to the table.

| Player | Betting Line | Implied Probability | True Probability | EV Ratio | Optimal Proportion | Growth Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | +700 | 0.125 | 0.233 | 1.86 | 0.123 | 4.5% |

| B | +170 | 0.370 | 0.454 | 1.23 | 0.133 | 1.5% |

| C | +550 | 0.154 | 0.110 | 0.72 | NA | NA |

| D | +800 | 0.125 | 0.050 | 0.45 | NA | NA |

| E | +450 | 0.182 | 0.043 | 0.24 | NA | NA |

Now, on to the new equation. Let's set up an equation to bet different proportions on players A and B at the same time. The general formulation for average growth rate is the ratio of the payout of an outcome to the power of the probability that the outcome happens. So, for this situation, the equation looks like this: \[\bar{G} = {(1 + {R}_{1}{p}_{1} - {p}_{2})}^{{s}_{1}} {(1 - {p}_{1} + {R}_{2}{p}_{2})}^{{s}_{2}} {(1-{p}_{1}-{p}_{2})}^{f}\] \[ = {(1 + 7{p}_{1} - {p}_{2})}^{0.233} {(1 - {p}_{1} + 1.7{p}_{2})}^{0.454} {(1-{p}_{1}-{p}_{2})}^{1-0.233-0.454}\] There are three possible outcomes: Player A is the MVP, Player B is the MVP, or neither of them are the MVP. So, the three terms in the formula are the payout ratios for these outcomes to the power of the likelihood of that outcome. It is important to remember that you need to subtract the proportion that you lose from your bet on Player B even if you win your bet on Player A and vice-versa.

In order to plug this equation into the maximization algorithm, we also need to tell it that these proportions must stay between 0 and 1 and that the sum of the proportions must be less than 1 (because you can't bet more than your whole bankroll). With these constraints, we get that the best proportions when betting on both player A and player B are 0.156 and 0.224 which result in a 9.2% growth rate! This is WAY better than betting on both individually. By making the likelihood of failure smaller, we can be more aggressive with the amounts that we bet. This leads me to wonder, what if also add in Player C? It would make sense if it doesn't help, but it is worth checking! Our equation would be:

\[\bar{G} = {(1 + {R}_{1}{p}_{1} - {p}_{2} - {p}_{3})}^{{s}_{1}} {(1 - {p}_{1} + {R}_{2}{p}_{2} - {p}_{3})}^{{s}_{2}} {(1 - {p}_{1} - {p}_{2} + {R}_{3}{p}_{3})}^{{s}_{3}} {(1-{p}_{1}-{p}_{2}-{p}_{3})}^{1-{s}_{1}-{s}_{2}-{s}_{3}}\]

When we plug in the values and put it into the algorithm in the Google Colab notebook, we get that the betting proportions for players A, B, and C should be 0.161, 0.240, and 0.021. This gives us a 9.4% growth rate! It is not much higher than before when we didn't add Player C, but it is higher, which means that this approach allows us to find value even in negative EV bets!So what if we also add Player D to the maximization algorithm? Their betting proportion is 0 and the rest of the values are the same as above. So this can only go so far, but we went from a 4.5% growth rate per bet when just betting on Player A, to a 9.4% growth rate when also betting on Players B and C, even though they are worse bets and one of them is negative EV! To remind you, these are based on real betting lines and predictions. However, we need to remember not to be too confident in our 'true' probabilities. And, don't forget to heed my warnings about futures. Still, this seems very promising!

Now that we've messed around with the formula a bit, let's write out a generic version. The growth ratio equals the multiplier that an outcome will have on your bankroll to the power of the likelihood of that outcome, multiplied by the same thing for all other outcomes. We can represent that like this: \[\bar{G} = \prod_{i}{{({Ratio}_{i})}^{{s}_{i}}}\] For our futures equations where we can bet on multiple outcomes for the same event, the ratio was \[{Ratio}_{i} = 1 + {R}_{i}{p}_{i} - \sum_{j \neq i}{{p}_{j}}\] and the outcomes were different players winning MVP.

So, what would happen if we apply these principles to betting on an NFL Sunday slate? There wouldn't be multiple bets that we can place on the same event, but there are many events that we can concurrently bet on. So what would the formula for that look like?

For betting on multiple games at once, each outcome is a different combination of game outcomes. That means that, for two games, the outcomes are: you win your bets on Games 1 and 2, you win on Game 1 but not Game 2, you win Game 2 but not Game 1, and you lose both bets. The formula for this is: \[G = {(1 + {R}_{1}{p}_{1} + {R}_{2}{p}_{2})}^{{s}_{1}{s}_{2}} {(1 + {R}_{1}{p}_{1} - {p}_{2})}^{{s}_{1}{f}_{2}} {(1 - {p}_{1} + {R}_{2}{p}_{2})}^{{f}_{1}{s}_{2}} {(1 - {p}_{1} - {p}_{2})}^{{f}_{1}{f}_{2}} \] To once again use realistic numbers, let's say that the moneyline for the team we like in game 1 is +120 (which has an implied probability of 0.455) and lets say that we think the true probability is 0.47 (which is a 1.5% edge). For game 2, let's have the moneyline be -120 (an implied probability of 0.545) and we think the true probability is 0.57 (a 2.5% edge). Using the maximization algorithm in the Google Colab notebook, we get the result for betting on each game individually. Those results are in the table below.

| Game | Betting Line | Payout Ratio | Implied Probability | True Probability | Edge | EV Ratio | Optimal Proportion | Growth Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | -120 | 0.833 | 0.545 | 0.57 | 2.5% | 1.045 | 0.028 | 0.05% |

| 2 | +120 | 1.20 | 0.455 | 0.47 | 1.5% | 1.034 | 0.054 | 0.12% |

Now that we have gone through all of the theory, let's see what happens when we try to bet on all of the NFL games on a Sunday. First, we only want to bet on games that we think are plus EV so that we can have a positive growth rate. Let's say that, on average, we think that there are 4 games that are plus EV. I will create some realistic numbers for these and two games that are negative EV so that we can plug them into the maximization algorithm and see what we get.

| Game | Betting Line | Payout Ratio | Implied Probability | True Probability | Edge | EV Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | +100 | 1.0 | 0.50 | 0.54 | 4.0% | 1.08 |

| 1 | -120 | 0.833 | 0.545 | 0.57 | 2.5% | 1.045 |

| 2 | +120 | 1.20 | 0.455 | 0.47 | 1.5% | 1.034 |

| 3 | -200 | 0.5 | 0.667 | 0.67 | 0.3% | 1.005 |

| 4 | -150 | 0.667 | 0.6 | 0.59 | -1.0% | 0.984 |

| 5 | +200 | 2 | 0.333 | 0.3 | -3.3% | 0.9 |

The outcomes will be defined the same as before: every combination of wins and losses for all of the games. So with 6 games, that will give us \({2}^{6}=32\) combinations. For each of these combinations, the multiplier an outcome will have on your bankroll is 1 plus the amount gained from each bet won, minus each bet lost. And the multiplier for each outcome will be to the power of the likelihood of that outcome. For especially fancy models, the outcome of the individual games could be correlated, which could give us even more of an edge. (For example, if Team 1 barely beats Team 2 in the previous week, your model might think the strengths of those two teams are similar. Therefore, if team 1 beats a good team this week, this fancy model would know that team 2 should now have a greater chance to win this week as well.) But for now, let's assume that the outcomes of each game don't affect the probabilities of the other games so we can just multiply the liklihoods of each game outcome together to get the overall likelihood of that combination of wins and losses. \[\bar{G} = \prod^{Outcomes}{\Big(1 + \sum_{g}^{Wins}{R}_{g}{p}_{g} - \sum_{g}^{Losses}{p}_{g}\Big)} ^ {\prod_{g}^{Wins}{s}_{g} \prod_{g}^{Losses}{f}_{g}}\] Here, \(Outcomes\) are every possible combination of winning and losing your bets and \(g\) is one of the games in the current combination. This looks complicated to write out, but thinking about it like this actually makes it easier to code. Using the maximization algorithm in the Google Colab notebook, we get the optimal betting proportions for all of the games which are shown in the following table.

| Game | Betting Line | Payout Ratio | Implied Probability | True Probability | Edge | EV Ratio | Optimal Proportion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | +100 | 1.0 | 0.50 | 0.54 | 4.0% | 1.08 | 0.08 |

| 1 | -120 | 0.833 | 0.545 | 0.57 | 2.5% | 1.045 | 0.054 |

| 2 | +120 | 1.20 | 0.455 | 0.47 | 1.5% | 1.034 | 0.028 |

| 3 | -200 | 0.5 | 0.667 | 0.67 | 0.3% | 1.005 | 0.011 |

| 4 | -150 | 0.667 | 0.6 | 0.595 | -0.5% | 0.984 | 0 |

| 5 | +200 | 2 | 0.333 | 0.3 | -3.3% | 0.9 | 0 |

Also notice that, once again, the optimal betting proportions for games 1 and 2 are the same whether betting on all of the games or just betting on them individually. I have found this to be generally true when betting on separate concurrent events. This means that, instead of needing to use the complicated algorithm, as long as you assume the outcomes of the games are uncorrelated, you can determine how much to bet on each game using the simple formula that we found before: \[p = s - \frac{f}{R} = s - \frac{1 - s}{R}\] As long as you know the true probability, you can now determine your optimal betting proportion with one simple calculation! But I haven't yet told you what the resulting growth rate is when you bet with all of the above proportions. Well, wait no longer. Betting these proportions will get us an average growth rate of 0.49%! Wait... less than 1 percent growth rate? Isn't that terrible? Well, the thing about growth rates is that they compound. This is our average growth per weekend. if we want to know what our growth rate is after the 18-game season, not including playoffs, we need to multiply the growth ratio by itself 18 times. Doing this brings our season growth ratio to \({1.0049}^{18}=1.093\) or a 9.3% growth rate! That is almost as much as the stock market averages in 52 weeks, and we did it in only 18! And maybe you have more or better edges or you also bet on player props, or you also bet during the playoffs, or you also bet on other sports. Your time investment could actually be worth it!

Here is where I give the disclaimer that we don't actually know the 'true' probabilities, so we can't be too confident. But if you are already betting, you must already think that you know the true probabilities better than the market, at least in some circumstances. So, as long as you can quantify what you think the true probability is you can just plug it into this equation \[p = s - \frac{1 - s}{R}\] to determine what proportion of your bankroll you should bet.

So, if you are betting, you've probably already spent the time finding edges and deciding which games to bet on. But isn't the point of all of that ultimately to grow your bankroll? So, make the best use of your hard-fought edges and optimize how much you bet!